She may have taken the kids with her on these adventures during the 1950s, 60s and 70s, but Maier was no Mary Poppins. Her young charges also gave her something of an alibi when she took them to the streets on what she called “shooting safaris”.

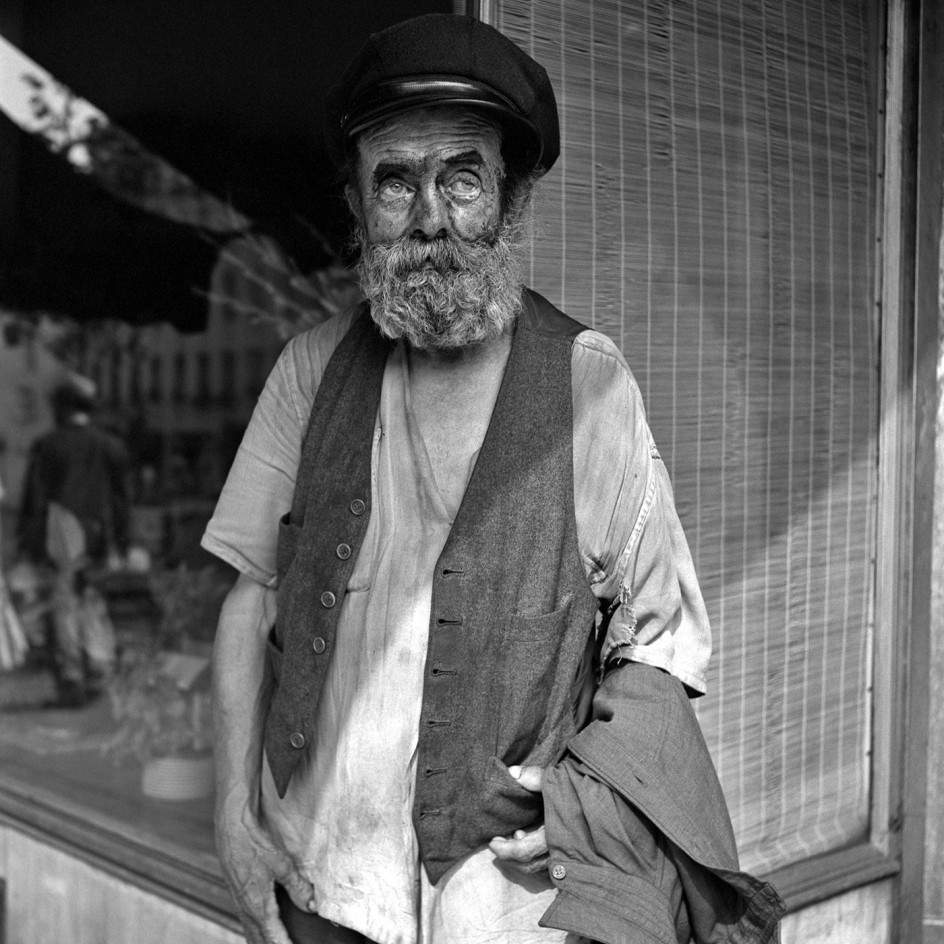

Her employers tolerated and indulged her until they couldn’t, and as the children grew things often got difficult, so Maier would move on. She put sturdy locks on her doors and filled these quarters and upper rooms with her boxes and the towers of newspapers she accumulated and never threw away. She holed herself up in the rooms she had been given by the families that employed her. Remembered too by some of her subjects and the people she wandered among with her camera and her funny, old-fashioned clothes on the streets of the cities where she had spent her peculiar double life as a children’s nanny and compulsive photographer.Īt some point Maier called herself a spy, and like any good spy she frequently changed the spelling of her name and gave herself different backstories depending on who asked. They filled boxes and suitcases and trunks, which spilled out their contents in avalanches of film rolls and envelopes, carefully preserved and lodged in storage facilities until the money ran out on their lockers and they were auctioned off.Įventually, and serendipitously, they began to come to light when Maier, late in life, was almost destitute and almost certainly mentally ill, more forgotten than remembered except to the families who had employed her as a nanny in Chicago, New York and Minneapolis.

Wildly prolific, and with an eye and an attitude all her own, she left more than 150,000 photographs, some printed by herself, many processed as negatives and yet more still undeveloped and left in their canisters.

V ivian Maier was unknown as an artist during her lifetime.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)